Liberal Pakistanis have criticized cricketer-turned-politician Imran Khan's opposition to a military operation against the Taliban. His alleged support to the Islamists has earned him the title, 'Taliban Khan.'

Recently, when the Pakistani Taliban nominated Imran Khan to engage in peace talks with Islamabad, liberal sections of society exclaimed, "See, we always said that Khan was one of the Islamists!"

Although Khan immediately refused to take part in the talks, the controversial "Taliban Khan" tag that he has earned over the years, got another endorsement.

Imran Khan is now one of the key players in Pakistani politics. His party came third in the May 2013 parliamentary elections and now rules the northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province bordering Afghanistan. He wants Islamabad to make peace with the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and sever its alliance with the US in the "war against terror."

"We will win this war if we disengage from the US," Khan recently told the media. "As long as the Taliban believe we are fighting the US war, they would declare jihad on us. This would be a never ending war," he added.

This is certainly a very different image of a liberal person who studied at the University of Oxford and played in the English cricket league in the 1980s. Back then, Khan was discussed in the British press as much for his sporting talent as for his alleged love affairs.

Khan went on to become one of the most successful cricketers Pakistan has ever produced, under whose leadership the nation won its first Cricket World Cup in 1992. He later engaged in philanthropic work in Pakistan and married British writer and campaigner Jemima Goldsmith. The wedlock, however, didn't last long.

Khan entered politics in the late 1990s, forming a party called Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (PTI). Although he was worshipped by millions in the country as a great cricketer, Khan was never considered a serious politician, even by his ardent fans, until 2011.

But now, for many of his fellow contrymen, the 60-year-old is the "last hope" in a country which is facing innumerable problems ranging from a non-functional economy to a protracted Islamist insurgency. For others, he is a right-wing politician who wants to appease the Taliban.

Who really is Imran Khan?

So how did a person, who was doubted even by members of his own political party as a political alternative to the two main political families, the Bhuttos and the Sharifs, become a force to reckon with in the Islamic Republic? Was it because of the support of the ubiquitous Pakistani army and its Inter-Services Intelligence agency (ISI), as his critics claim, or was it the relentless political campaigning that Khan has been doing for more than 16 years? Khan's supporters believe it is the latter.

"Khan's stance on corruption, terrorism and nepotism in Pakistani politics has struck a chord with the masses, which are fed up with the traditional ruling elite. He has no corruption charges on him, no foreign assets," claims PTI activist in Islamabad, Khawar Sohail.

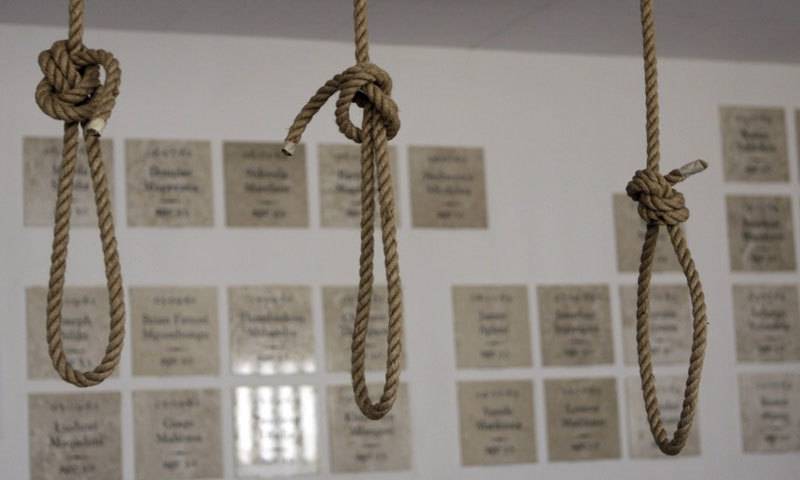

Representatives of the Pakistani government and the Taliban met in Islamabad for peace talks

Khan's PTI has been in power for almost , 1 year and eight months, yet critics state that most of his election promises have not been fulfilled.

"The government in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province has not delivered anything to people. Corruption and nepotism are rampant and there hasn't been any significant development work in the past eight months," said Qasim Jan, a student in the northwestern city of Peshawar.

"Khan has only focused on protesting US drone strikes in the northwestern tribal areas, blocking the NATO supply route to Afghanistan, and coming up with all sorts of excuses in support of the militants," he added.

Islamabad-based writer, Arshad Mahmood, agrees: "Things are pretty much the same as they were in the past. Khan's party workers consider themselves to be above the law and won't cooperate with the administration. If the PTI officials don't obey the law, how will the governance be improved?," asked Mahmood.

But Khan's supporters, which comprise mainly the Pakistani youth, feel his administration is being unfairly criticized.

"The government has made great strides into a faster and more effective judicial system. The education budget of the province is much bigger than in other provinces. Yes, there are problems, but things are improving," Zakria Zubair, a young entrepreneur in Islamabad, told DW. The 29-year-old PTI supporter also says that Imran Khan is playing the role of a competent opposition leader in the country's lower house of parliament.

source ; http://www.dw.de/pakistan-school-massacre-to-further-strengthen-armys-resolve-to-fight-ttp/a-18134203

|

| Imran Khan:Aka Taliban Khan Flirting with the Taliban |

Recently, when the Pakistani Taliban nominated Imran Khan to engage in peace talks with Islamabad, liberal sections of society exclaimed, "See, we always said that Khan was one of the Islamists!"

Although Khan immediately refused to take part in the talks, the controversial "Taliban Khan" tag that he has earned over the years, got another endorsement.

Imran Khan is now one of the key players in Pakistani politics. His party came third in the May 2013 parliamentary elections and now rules the northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province bordering Afghanistan. He wants Islamabad to make peace with the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and sever its alliance with the US in the "war against terror."

|

| Power and Money Hungry : Imran Khan married Jewish Jemima Goldsmith in 1995 |

"We will win this war if we disengage from the US," Khan recently told the media. "As long as the Taliban believe we are fighting the US war, they would declare jihad on us. This would be a never ending war," he added.

This is certainly a very different image of a liberal person who studied at the University of Oxford and played in the English cricket league in the 1980s. Back then, Khan was discussed in the British press as much for his sporting talent as for his alleged love affairs.

Khan went on to become one of the most successful cricketers Pakistan has ever produced, under whose leadership the nation won its first Cricket World Cup in 1992. He later engaged in philanthropic work in Pakistan and married British writer and campaigner Jemima Goldsmith. The wedlock, however, didn't last long.

Khan entered politics in the late 1990s, forming a party called Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (PTI). Although he was worshipped by millions in the country as a great cricketer, Khan was never considered a serious politician, even by his ardent fans, until 2011.

|

| Cant be Away from Cameras ?? Cricketer Play boy and now Taliban Khan |

But now, for many of his fellow contrymen, the 60-year-old is the "last hope" in a country which is facing innumerable problems ranging from a non-functional economy to a protracted Islamist insurgency. For others, he is a right-wing politician who wants to appease the Taliban.

Who really is Imran Khan?

| Play Boy and Play Girl Perfect Couple now Deceiving Pashtuns |

So how did a person, who was doubted even by members of his own political party as a political alternative to the two main political families, the Bhuttos and the Sharifs, become a force to reckon with in the Islamic Republic? Was it because of the support of the ubiquitous Pakistani army and its Inter-Services Intelligence agency (ISI), as his critics claim, or was it the relentless political campaigning that Khan has been doing for more than 16 years? Khan's supporters believe it is the latter.

"Khan's stance on corruption, terrorism and nepotism in Pakistani politics has struck a chord with the masses, which are fed up with the traditional ruling elite. He has no corruption charges on him, no foreign assets," claims PTI activist in Islamabad, Khawar Sohail.

Imran Khan Rise to Power by Punjabi Establishment / GHQ and its Made Taliban

But some observers argue that Khan is backed by Pakistan's right-wing groups, in particular the military establishment, because of his "soft" stance on the Taliban and other Islamist militants. His rise in Pakistani politics, they claim, is due to his "good relations" with the ISI. Khan agrees with the organization's position on matters such as Afghanistan and Pakistan's national security, they say.

Amima Sayeed, a development researcher from Karachi, believes that Khan, most definitely, supports right-wing extremists. He has not made it secret.

"When the Swat peace deal between the government and the Taliban was introduced in 2009, Imran Khan was the first politician to support it. His collaboration with the Islamic Jamaat-e-Islami party is also a proof of his right-wing agenda," she told DW.

"He might not sound like a religious political leader of the Jamaat-e-Islami or the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, but his views about the region, the world, and in particular about the militant groups in Pakistan, are sympathetic if not supportive of the religious right," Owais Tohid, a journalist for the Wall Street Journal in Karachi, agrees. "He opposes a military crackdown on the militants and dismisses the idea that there has been an increase in the homegrown jihadist culture in Pakistan over the years."

Eight months of Failed Government in power

But some analysts say that the debate about Khan's Islamist or liberal credentials is actually taking the spotlight away from his performance as a politician and the leader of a party which governs an important province of the country.

Khan promised speedy justice and an end to corruption in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province after taking its reins. During the election campaign, he also said his party would curb violence and bring peace.

But some observers argue that Khan is backed by Pakistan's right-wing groups, in particular the military establishment, because of his "soft" stance on the Taliban and other Islamist militants. His rise in Pakistani politics, they claim, is due to his "good relations" with the ISI. Khan agrees with the organization's position on matters such as Afghanistan and Pakistan's national security, they say.

Amima Sayeed, a development researcher from Karachi, believes that Khan, most definitely, supports right-wing extremists. He has not made it secret.

|

| Need any ID Card ?? |

"When the Swat peace deal between the government and the Taliban was introduced in 2009, Imran Khan was the first politician to support it. His collaboration with the Islamic Jamaat-e-Islami party is also a proof of his right-wing agenda," she told DW.

"He might not sound like a religious political leader of the Jamaat-e-Islami or the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, but his views about the region, the world, and in particular about the militant groups in Pakistan, are sympathetic if not supportive of the religious right," Owais Tohid, a journalist for the Wall Street Journal in Karachi, agrees. "He opposes a military crackdown on the militants and dismisses the idea that there has been an increase in the homegrown jihadist culture in Pakistan over the years."

Eight months of Failed Government in power

But some analysts say that the debate about Khan's Islamist or liberal credentials is actually taking the spotlight away from his performance as a politician and the leader of a party which governs an important province of the country.

Khan promised speedy justice and an end to corruption in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province after taking its reins. During the election campaign, he also said his party would curb violence and bring peace.

|

| Chief Trainer of Taliban Mullah Sami and Iran Siddique a Taliban Sympathizer in Paki Media |

Representatives of the Pakistani government and the Taliban met in Islamabad for peace talks

Khan's PTI has been in power for almost , 1 year and eight months, yet critics state that most of his election promises have not been fulfilled.

"The government in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province has not delivered anything to people. Corruption and nepotism are rampant and there hasn't been any significant development work in the past eight months," said Qasim Jan, a student in the northwestern city of Peshawar.

"Khan has only focused on protesting US drone strikes in the northwestern tribal areas, blocking the NATO supply route to Afghanistan, and coming up with all sorts of excuses in support of the militants," he added.

|

| Pakhtunkhwa Governance |

Islamabad-based writer, Arshad Mahmood, agrees: "Things are pretty much the same as they were in the past. Khan's party workers consider themselves to be above the law and won't cooperate with the administration. If the PTI officials don't obey the law, how will the governance be improved?," asked Mahmood.

But Khan's supporters, which comprise mainly the Pakistani youth, feel his administration is being unfairly criticized.

"The government has made great strides into a faster and more effective judicial system. The education budget of the province is much bigger than in other provinces. Yes, there are problems, but things are improving," Zakria Zubair, a young entrepreneur in Islamabad, told DW. The 29-year-old PTI supporter also says that Imran Khan is playing the role of a competent opposition leader in the country's lower house of parliament.

source ; http://www.dw.de/pakistan-school-massacre-to-further-strengthen-armys-resolve-to-fight-ttp/a-18134203